Table of Contents

Of the three primary financial statements, the Statement of Cash Flows is arguably the most honest. While the Income Statement can be shaped by accounting estimates and non-cash items, the movement of cash is a hard, cold reality. It’s the ultimate truth teller of a company’s financial health. Yet, a perspective forged through my years of navigating financial systems reveals a persistent irony: it is also the statement that many finance teams find the most challenging to prepare accurately and efficiently.

The difficulty often lies in bridging the gap between the accrual based world of the general ledger and the cash based reality of operations. Modern ERP systems have automated much of the accounting cycle, but generating a clean Statement of Cash Flows often remains a surprisingly manual and error prone part of the financial close.

A Strategic Reframing of the Three Activities

We all learn the three core sections, but their true value emerges when viewed through a strategic, rather than purely academic, lens. It’s about understanding the story each section tells.

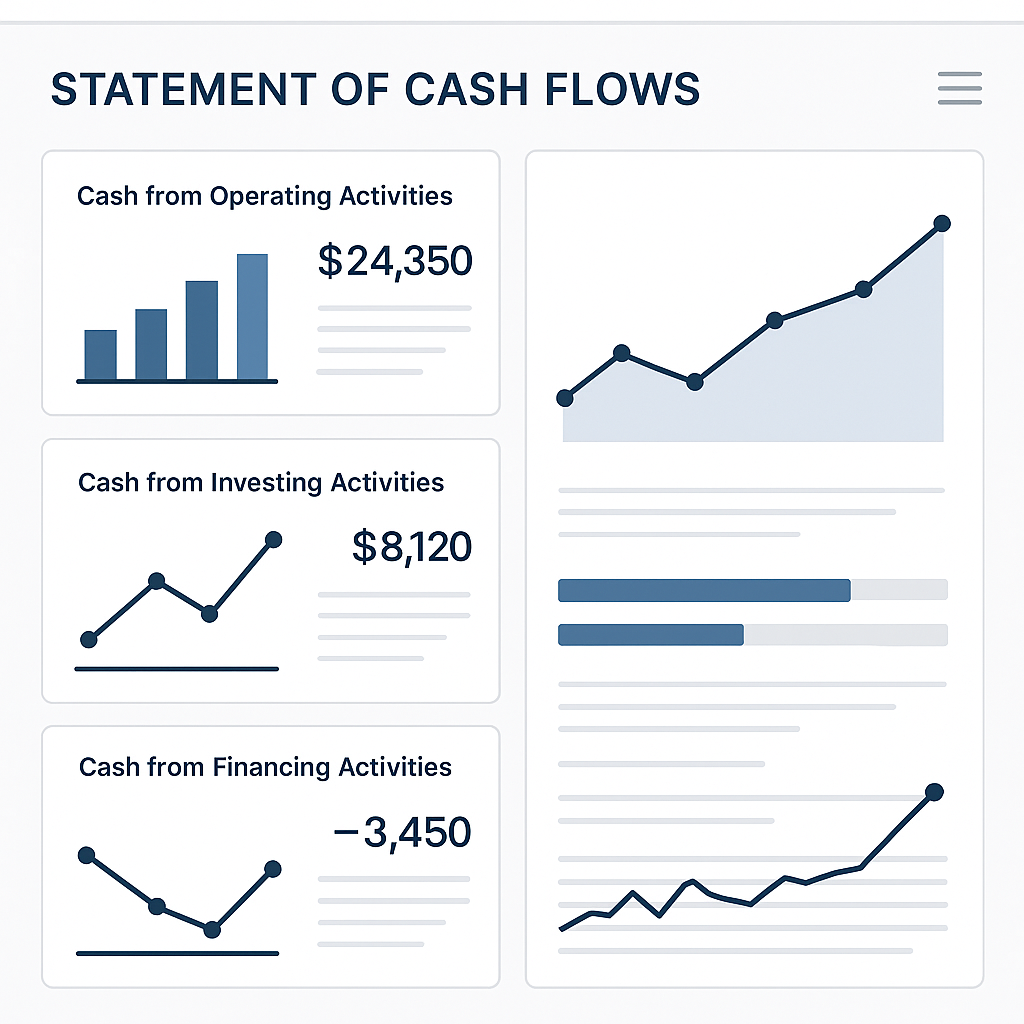

- Cash Flow from Operating Activities (CFO): This is the engine room. Does the core business (selling goods or services) actually generate cash, or does it consume it? A healthy, sustainable business must generate positive cash flow from its operations over the long term. A consistent divergence between net income and operating cash flow is a major red flag that demands investigation.

- Cash Flow from Investing Activities (CFI): This section tells you about the future. Where is the company placing its bets? Is it investing heavily in new property, plant, and equipment (CapEx)? Is it acquiring other companies? Or is it selling off assets? This is strategy made tangible in dollars and cents.

- Cash Flow from Financing Activities (CFF): This is the fuel tank. How is the company funding its operations and investments? Is it taking on debt, issuing stock, or paying down loans? Is it returning cash to shareholders through dividends or buybacks? This section reveals the company’s capital structure strategy and its relationship with its investors and creditors.

The Indirect Method: More Than a Reconciliation

The indirect method for preparing the operating section is by far the most common, but it’s often treated as a mechanical reconciliation exercise. That’s a missed opportunity, isn’t it? It’s actually a powerful diagnostic tool. The adjustments to reconcile net income to cash flow provide critical insights into a company’s working capital management.

For example, a large increase in accounts receivable might look good on the income statement as revenue, but it’s a drain on cash. Similarly, a ballooning inventory consumes cash. These non-cash adjustments unmask the true liquidity impact of operational decisions. Insights distilled from numerous financial analyses show that a careful review of these adjustments often reveals more about a company’s operational health than the net income figure alone.

The Systemic Challenge: Why ERPs Can Struggle

A recurring challenge I’ve observed in many ERP implementations is that generating a Statement of Cash Flows is rarely a push button affair. Why is that? The system tracks debits and credits, but it doesn’t always have the native context to classify the nature of the cash movement for investing and financing activities.

This often requires a well-designed Chart of Accounts with specific accounts for non-cash transactions and investing/financing activities. Furthermore, significant non-cash transactions (like acquiring an asset by issuing debt) must be properly tagged or handled to be included in the disclosures, but excluded from the main body of the statement. Without this thoughtful architectural design upfront, finance teams are left to perform significant manual analysis and reclassification outside the system.

The Ultimate Metric: Free Cash Flow

Beyond the required reporting, the Statement of Cash Flows provides the inputs for what many analysts consider the ultimate measure of financial performance: Free Cash Flow (FCF). Typically calculated as Cash Flow from Operations less Capital Expenditures, FCF represents the cash a company generates after accounting for the investments needed to maintain or expand its asset base. This is the cash available to be returned to investors or used for strategic initiatives.

An organization that consistently generates strong, positive FCF has financial flexibility and resilience. This is a far more powerful indicator of health than reported earnings alone.

The Statement of Cash Flows should be viewed as more than a compliance requirement. It’s a strategic diagnostic tool that provides a clear, unvarnished view of a company’s ability to generate cash, fund its growth, and meet its obligations. For leaders and analysts, mastering its interpretation is fundamental to understanding a business’s true financial story.

For further discussion on enterprise systems and financial analysis, I invite you to connect with me on LinkedIn.